A cornerstone of credit union advocacy is ensuring central bank policy aligns with Main Street realities.

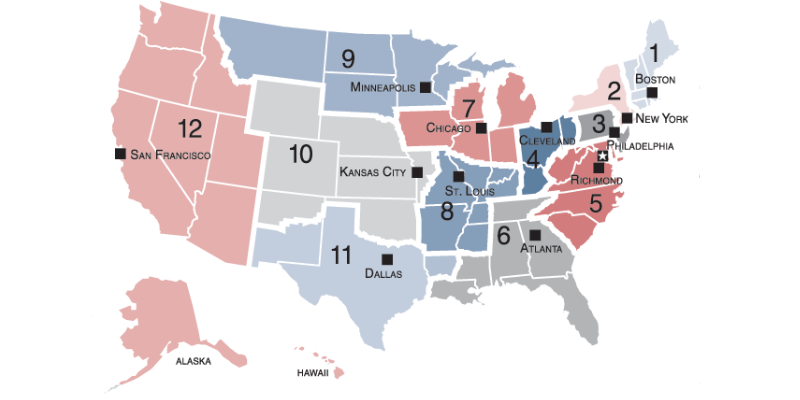

The Federal Reserve can’t be everywhere at once, so it relies on its 12 regional banks, or districts, for local perspective. In turn, regional presidents depend on advisory councils to keep them connected to what’s happening on the ground. That structure creates a valuable channel for credit union leaders to share their experiences and insights directly with the Fed.

Each district organizes its councils a little differently, but they commonly include Community Depository Institutions Advisory Councils (CDIACs), Community Advisory Councils (CACs), industry-specific councils, and state or regional boards. Members generally serve three-year terms, acting as ears to the ground for the Fed on issues that affect communities and financial institutions alike.

Chris Parker is president and CEO of Lighthouse Credit Union ($2.0B, Dover, NH), a role he has held since June 2021. He is also a member of the Fed’s First District’s CDIAC, which oversees Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.

“To me, it’s all about the impact we can make in the community and the state through the work we’re doing at Lighthouse,” Parker says.

In Ohio, which makes up majority of the Fourth District, John Demmler serves on the Shenango-Mahoning Valley Business Advisory Council. Currently the CEO of 7 17 Credit Union ($1.8B, Warren, OH), Demmler joined the industry 10 years ago after previously working at both large multinational banks and a community bank.

“That community bank experience really shaped my perspective on what kind of impact a financial institution can have on a community,” Demmler says. “People say it often: Bankers move to credit unions, but you don’t see many people going the other way. There’s a reason for that.”

Peer Recommended, Fed Approved

The credit union industry is built around relationships, so it should come as no surprise that it was Demmler and Parker’s relationships with their peers and communities that led to their advisory council positions.

Parker says he first became aware of the opportunity through Lighthouse CFO, Neil Gordon.

“I actually knew a peer who was on the CDIAC,” Parker says. “I reached out to them about the experience, and it sounded great.”

Lighthouse Credit Union submitted a formal nomination for Parker, after which Susan M. Collins, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, invited him to join the CDIAC in March 2024.

The council is made up of 12 members from varying financial institutions representing the whole of New England. They meet twice a year in April and October. Parker is one of two members from New Hampshire. He is also only one of two credit union leaders currently serving.

“Credit unions have a different experience since we’re member-owned and close to our communities,” Parker says. “That makes my perspective as a New Hampshire credit union leader pretty unique.”

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland recruited Demmler last fall, and he formally joined the Shenango-Mahoning Valley Business Advisory Council in January 2025. The president of the local Chamber of Commerce contacted the CEO because they wanted to recommend him for the position. Demmler then met with Dr. Russell Mills, the Fed’s Senior Regional Officer, who determined Demmler was a good fit.

The advisory council Demmler serves on is one of multiple dedicated to representing businesses across the region. Meetings occur quarterly rather than twice a year and bring together dozens of representatives across diverse sectors, including manufacturing, construction, trades, and retail.

“There’s even someone who runs an ice cream shop,” Demmler says. “It’s always fun to hear how ice cream sales reflect what’s going on in the economy.”

The Importance Of Federal Reserve Advisory Boards

Although different in cadence and composition, the councils Demmler and Parker serve on have a similar two-part function. Members share feedback, insights, and concerns through surveys and dialogue that help influence economic decisions. In turn, council members also gain insight from the Federal Reserve and one another.

“You don’t get inside trading secrets,” Parker is quick to note. “Everything is scripted when President Collins gives remarks, but you are in the room and get to hear directly from each other.”

For example, last year the Boston Fed’s CDIAC discussed housing and lending, and Parker advocated for the work Lighthouse Credit Union was doing in New Hampshire.

“We were the first lender in the state to offer accessory dwelling unit (ADU) loans,” he says. “I got to speak about how those were impacting members and how we were trying to innovate to address the housing crisis.”

That sparked interest from a peer in Rhode Island who wanted to talk about it with their housing secretary and asked Parker to share more.

“Advocating in that room led to ripple effects beyond New Hampshire, which I think is one of the best parts of serving on the CDIAC,” Parker says.

Housing is also a significant challenge the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland discusses, as it’s one of the biggest barriers to bringing new jobs to Northeast Ohio.

“We hear it from businesses trying to recruit talent: If people can’t find homes, they can’t relocate here,” Demmler says.

When it comes to other insights council members share with one another, Demmler says he can work with his team to adjust 7 17’s strategy around business banking products and services when he hears business leaders talk about specific pain points they’re facing.

“Rather than guessing what businesses might need, we’re hearing it directly from them,” Demmler says. “That feedback loop has been invaluable.”

The Ripple Effect

Tariffs have dominated economic discussions this year, and Demmler says his fellow council members share a wide range of attitudes.

“Some businesses are hurt by them, citing higher costs, disrupted supply chains, less ability to compete,” he explains. “Others aren’t impacted at all. And some actually benefit and love tariffs.”

The Ohio cooperative’s CEO says hearing all those perspectives side by side is the exact kind of ground-level feedback the Fed is looking for, and Fed presidents take that input into FOMC discussions when deciding interest rate policy.

Lean in, pay attention, and be involved. It has a ripple effect, even if you don’t see it right away.

“When she hears that some businesses are struggling with inflationary pressures from tariffs, that might factor into whether lowering rates could help consumers offset those costs,” Demmler says. “It’s all about balancing competing needs, and that local input is key.”

Although Parker did not know what to expect, he found that Dr. Collins and the team at the Boston Fed are welcoming and want to know what’s going on.

“There’s always a give and take,” he says. “They’re listening to us, but they’re also giving back. That’s the important part of the relationship: Lean in, pay attention, and be involved. It has a ripple effect, even if you don’t see it right away.”

Tariffs, inflation, and interest rates might dominate the headlines, but for credit union leaders on Fed advisory councils, the role goes deeper than parsing economic policy. It’s about ensuring the cooperative perspective is part of the national conversation.

Demmler says that means leaning into the mission and being intentional about addressing pressing local issues.

“When you do that, people notice,” he says. “They want problem solvers and doers at the table, not just talkers. I don’t want to sit on a board just to eat a chicken dinner once a quarter. I want to make a meaningful impact.”

Parker agrees, noting that the real measure of success isn’t what the Fed hears, but how that dialogue translates back to the credit union and its members.

“What does that mean to your balance sheet?” he asks. “More importantly, what does that mean to your members’ lives? That’s the key.”