Top-Level Takeaways

-

Balance sheet management helps credit unions better understand how current and future economic scenarios will affect assets and liabilities.

-

For this year and beyond, credit unions should monitor rates, liquidity, and technology costs.

CU QUICK FACTS

Ent Credit Union

Data as of 12.31.18

HQ: Colorado Springs, CO

ASSETS: $5.6B

MEMBERS: 338,834

BRANCHES: 32

12-MO SHARE GROWTH: 9.9%

12-MO LOAN GROWTH: 14.0%

ROA: 1.10%

Interest rates and fixed costs are rising, liquidity is shrinking, and the U.S. economy is showing signs that it could soon slow down. These factors and others underscore uncertainty in today’s economic climate, which can prove challenging to credit unions. However, organizations that manage their balance sheets to absorb potential shocks are well positioned to report positive performance in any environment.

In practice, balance sheet management involves forecasting a credit union’s cash flow and other behaviors for each asset and liability in a variety of scenarios. MJ Coon, chief financial officer of Ent Credit Union ($5.6B, Colorado Springs, CO), describes balance sheet management as planning to ensure the credit union remains safe and sound in any interest rate or economic environment.

For Ent, it looks at how economic changes will affect its net economic value (NEV) ratio and its net interest income.

Net Economic Value (NEV): A measurement of the present value of assets minus the present value of liabilities, plus or minus the present value of expected cash flows on off-balance sheet instruments.

Net interest income: The difference between the revenue a financial institution generates from its assets and the expenses associated with paying its liabilities.

Say we’re in a certain yield curve environment, whether steep or flat, Coon says. We run what-if’ scenarios and determine where we are from a safety and soundness standpoint if, for example, X% of our core deposits leave the credit union, we sell off X% of our mortgage or auto loan portfolios, or we run a deposit special and attract a certain amount of business.

Ent asks its third-party advisory firm, ALM First, to process four to five of these scenarios at the end of the quarter and sends a report to its asset-liability committee (ALCO). The credit union also runs one-off scenarios when it has an idea it really wants to test.

Sometimes the scenarios might not have a huge effect, but we run it for our peace of mind, Coon says.

Recently, Ent has run scenarios to determine what would happen if the yield curve inverted, if members reduced the speed at which they prepaid loans, and if Ent raised deposit rates.

Everyone wants to raise deposits right now, the CFO says. We run scenarios on different deposit pricing strategies to see what impact that will have.

These are three scenarios for which Ent has recently run what-if modeling, but the credit union is monitoring many more. Ent, however, is just one credit union under a specific set of economic pressures that differ in different degree from most of the other 5,500 credit unions in the industry. But for 2019 and beyond, credit unions from Colorado Springs, CO, to Coral Springs, FL, and everywhere in between will need to monitor macro-economic factors to determine whether they need to change the way they do business.

No Home Runs

There is no cookie-cutter approach to balance sheet management, says Cindy Nelson, senior vice president at EasCorp.

Credit unions have different risk profiles, and depending on those risk profiles, they will have different strategies and will require different recommendations, she says. Although there are broad factors affecting credit unions, i’s hard to make broad recommendations.

But those factors are worth tracking.

One such factor is interest rates. The Federal Reserve increased its federal funds rate four times in 2018 and many anticipated another two to three increases in 2019. However, the Fed didn’t raise rates in the first quarter of 2019 and in March voted to keep the rate at its current range for the foreseeable future, possibly hinting at a cut by the third quarter.

No one knows where rates are going or how fast, Nelson says.

Without knowing whether rates will increase of decrease, credit unions must manage their books in a way that satisfies either possibility.

One thing we’ve learned over the years is to plan for either direction, Coon says. That means you won’t hit a homerun, but you’ll be solid and secure.

Credit unions are not in the home run-hitting business, anyway, Nelson says. They’re in the risk-management business, which means they need to understand, first, are they comfortable with the risk they currently have, and, second, how much risk is too much?

For example, approximately one-fifth of the industry has a loan-to-share ratio greater than 90%. As rates inch up from historic lows, credit unions have the opportunity to increase their deposit rates to attract much needed liquidity. But what could that cost the credit union?

We could create a 5% CD special betting that rates continue to rise, Coon says. But what happens if they don’t and we’re paying 5% for years?

A popular CD special drew in $80 million as well as rate chasers looking for a good deal during bad times. Find out what this credit union wish it knew before it grew. Read it here.

That might be an extreme example, but it highlights an important consideration in managing interest rate risk.

What I preach all the time is, What if we’re wrong?’ Coon says. Chances are that rates are going to go a certain way. But we’re a conservative shop, so we’re not going to bet the farm on chances are.’

A Question Of Liquidity

The average loan-to-share ratio at U.S. credit unions in the fourth quarter of 2018 was 85.5%. This is the highest rate in the past two decades, according to data from Callahan Associates, but even that doesn’t tell the full story.

In the fourth quarter of 2018, 395 credit unions reported loan-to-share ratios greater than 100%. A full 1,124 reported ratios greater than 90%. Ten years ago, those numbers were 362 and 981, respectively. Ten years before that, they were 231 and 807.

This ratio continues to rise, and credit unions are not interested in slowing down their loan demand, says Travis Goodman, advisory services principal at ALM First, a financial advisory services provider for banks and credit unions.

Credit unions often define themselves as a financial institution that originates loans and provides credit to members in need, which can make it difficult to turn off the loan engine. And although the industry’s increased loan volume can signal economic bullishness, share growth has not kept pace with loan growth, putting a squeeze on liquidity.

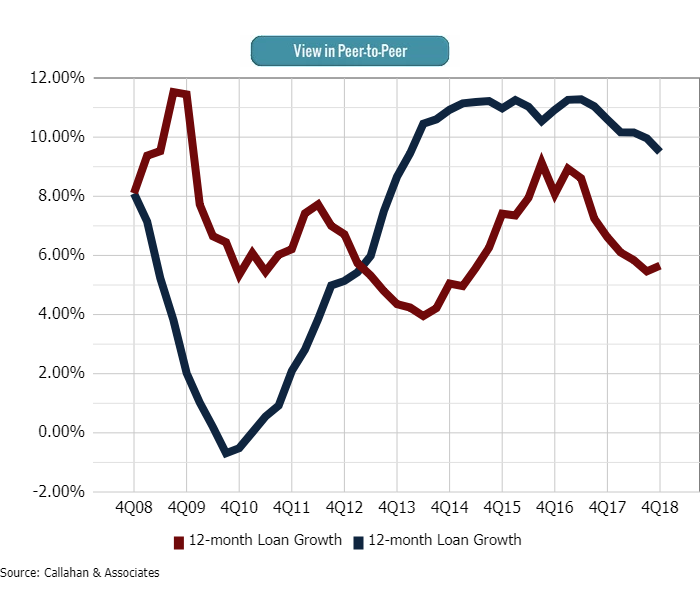

LOAN AND SHARE GROWTH

FOR U.S. CREDIT UNIONS | DATA AS OF 12.31.18

Callahan Associates | CreditUnions.com

Credit union loan growth surpassed share growth in 2012 and has remained higher ever since.

This squeeze isn’t a problem that rises to the level of crisis, Goodman says, because depositors aren’t moving their funds away from credit unions. Rather, i’s a question of asset liability management. As such, he suggests asking how to manage in the best economic interest of the organization.

Whether in the form of member deposits, borrowings, or, for some, non-member deposits, credit unions pay for sources of liquidity they subsequently use to fund new loan originations. To attract more deposits, credit unions can raise rates maybe not to the degree of a 5% CD special but enough to kick-start activity.

However, some credit unions are reluctant to increase rates to raise or hold onto deposits, says Deborah Rightmire, ALM and financial analysis director at the Cornerstone Credit Union League. That doesn’t fare well for balance sheet management.

When loans are increasing and deposits are stagnant or declining, at some point, liquidity becomes an issue, the director says.

Goodman at ALM First agrees.

They’ll either need to shut down the loan machine, which doesn’t seem likely, or find another source of liquidity, he says.

Although a threat to liquidity is a serious matter, Rightmire cautions against choosing a source to raise deposits without fully evaluating it.

Each source of liquidity comes with different pros and cons, she says. Credit unions must evaluate these to pick the choice that best meets their need.

One source of liquidity that holds potential for credit unions is loan participations, although these transactions are more complicated than simply matching a buyer and seller.

Credit unions need to understand what they are buying and perform their own due diligence and underwriting of the loan, Nelson at EasCorp says. Is it a fair price? Are they being compensated properly? Plus, how do they account for it?

On the other side, Goodman says the economics might not be in the seller’s favor. As credit unions become more loaned out, a time could come when there are more sellers than buyers, which will drive down demand and drive up cost.

When tha’s the case, sellers are forced to offer attractive rates to bring in the buyers, Goodman says. If a credit union is selling loans at a loss or a high economic cost, it requires the cooperative to leverage capital. That can be an expensive funding source compared to raising deposit rates.

Managing For The Long Term

Uncertainty around rates and squeezes to liquidity are two of the more pressing economic factors affecting the credit union balance sheet, but they are not the only two.

Of the four stages of the economic cycle, the U.S. economy is in a prolonged period of expansion. Economists expect growth will slow in the future, which doesn’t necessarily mean a recession is imminent, but credit unions are well served to plan now for a credit event in the next 18 to 24 months. To do that, Goodman suggests pairing CECL analysis with robust capital scenario projections to understand just how much credit risk is present in an institution’s balance sheet.

If you see, with a credit loss storm brewing, that you will still grow capital, you might need to put more capital to work, he says. If you are concerned about a credit event, pricing if the first place to look.

According to Goodman, credit unions underprice autos, in particular, because they set rates based on their local market rather than off the national market. Tha’s one reason he believes autos might cause trouble down the road.

If you offer a higher rate and volumes drop, tha’s not necessarily a bad thing, Goodman says. If you price right, you have less of a worry down the road because you’re pricing is appropriate.

Even as rates change today, a credit union must still think about balance sheet management in the long term, EasCorp’s Nelson advises. They must take a holistic view of assets and liabilities, understand where to take risks and where to complement those risks with safe, economic sources of liquidity, and, above all else, remember the member.

Credit unions have to stay true to their philosophy of people helping people, says Rightmire at the Cornerstone League. Our primary goal is to meet members’ financial needs.