NCUA’s proposed RBC rule presumes the agency has significant capabilities to identify future risk, document potential shortfalls, and accurately manage uncertainties.

A real-world test of these capabilities is the annual performance of the NCUSIF. NCUA released the 2014 audit on Feb. 13, 2015, with no briefing or explanatory information that would provide insight about the management of the credit union system’s collective capital.

A review of the audit results brings to light why the agency offered no insight. The accounting information obscures the real-world results and portrays an agency continuously changing its estimates in material and significant ways without explanation.

Current Period Results Versus The Official Accounting Presentation

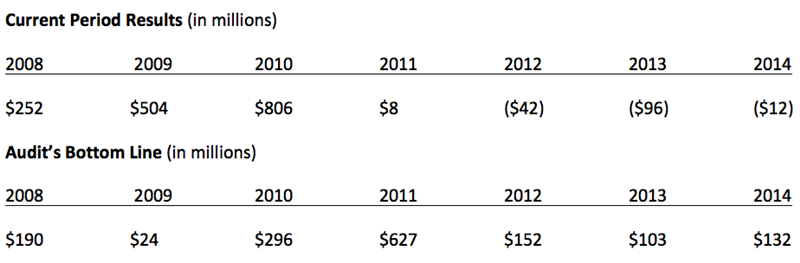

Comparing the past seven years’ reported results with the actual activity that occurred during the year presents two very different pictures of the fund’s bottom line and overall trends.

Current period results are the actual revenue received, expenses paid, and net losses (cash paid less recoveries) incurred during the year.

The difference between the real economic/financial results and the accounting results show the NCUSIF significantly understated the bottom line in the two years of the crisis and has consistently overstated the outcome since then. Not coincidentally, the two premiums assessed by the NCUIF occurred in 2009 for $727 million and in 2010 for $930 million. Both of these current period revenue items are included in the above summaries.

From the two number series it is clear the NCUSIF has reported more positive accounting results than what the actual economic outcomes were for the past four years. During these most recent four years, the fund has had a cumulative loss of $142 million.

This operating outcome presents a different financial trend and challenge for the NCUSIF’s management than the accounting picture presents. So what is the reason for the difference? And what does this indicate about NCUA’s ability to assess, estimate, and manage its fundamental risk responsibilities?

The Accounting Re-estimates

The most important judgment the NCUSIF’s management makes is the amount to set aside in loss reserves. This is an estimate. The audit report devotes a full page to the process and describes it in three different places.

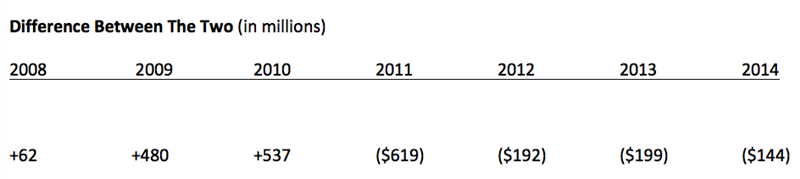

However, the data shows that the amount in the reserve account at the year-end audit date has no relation to the actual losses incurred in the fund. The most recent example is at December 2013. The reserve held $221 million, which was 485% of the actual losses of $45.6 million that were incurred in 2014.

The graph below demonstrates that year-end reserves to actual losses are all over the map, with the most extreme disconnect occurring in 2010. That year-end reserve of $1.2 billion was 1,300% more than the actual losses in 2011.

Only in 2008, when NCUA employed an auditor other than KPMG, is the loss reserve within striking distance 192% of the next year’s actual loss.

Inflated Losses Affect Accounting Numbers And Credit Unions

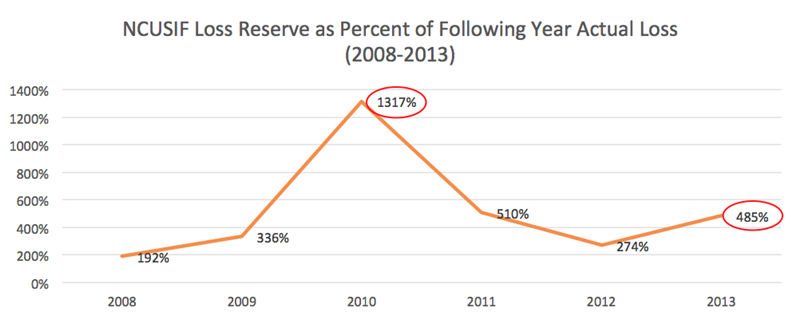

As every CEO/CFO knows, the primary way to increase the loss reserve is to expense from current income an amount to add to the reserve. Realized losses are then deducted as incurred from the reserve, not the income statement. Recoveries are added back. Loss provision expense is run through the income statement and is the primary factor accounting for the difference between the real operating results and the accounting numbers presented above.

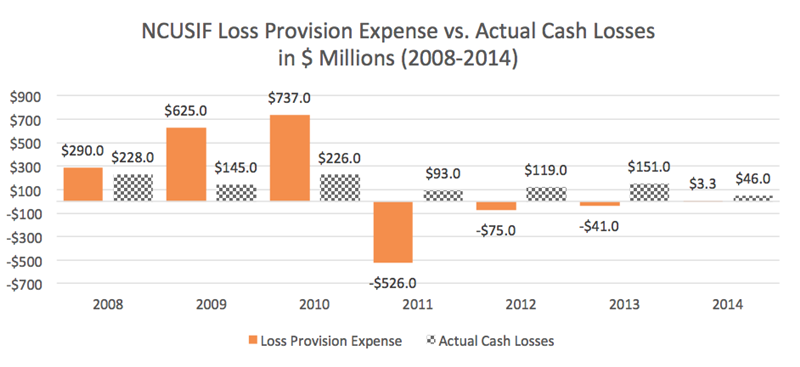

For the past seven years this expense is as follows:

The problem, and the key issue for assessing NCUSIF’s management, is that this expense has shown no relationship to what actually occurred in the current or subsequent years.

The two largest differences occurred in 2009 and 2010, years in which the NCUA assessed premiums on credit unions. These premiums were not justified by the current year’s real loss experience or subsequent events. Moreover, NCUA imposed this $1.7 billion premium expense on credit unions in the midst of the financial crisis.

Just as credit unions were fulfilling their critical counter-cyclical role of expanding credit to members in the middle of the greatest financial downturn since the depression, NCUA removed $1.7 billion of credit union capital. At a 7% well-capitalized level, this expense out of capital took away $24 billion of lending potential for credit union members.

Moreover, these unneeded premiums added an expense at a time when credit unions were themselves struggling with loan losses and trying to minimize costs. Finally, NCUA transferred $462 million of these unnecessary premiums to the TCCUSF because the NCUSIF equity ratio at three subsequent year-ends exceeded the fund’s 1.3% normal operating level. The December 2014 audit of the TCCUSF shows it is also over-reserved by at least $240 million.

The chart below shows how this NCUSIF provision expense has had no relationship to actual losses throughout the past seven years. The only year the accounting event is close to real events is 2008.

2014 Audit: Dj Vu All Over Again

But surely, five years after the crisis and with the benefit of hindsight and more normalized data, NCUSIF’s management is getting better at this estimation effort.

Wrong.

The reversals of accounting estimations actually increased and had a significant impact on the reported bottom line for 2014.

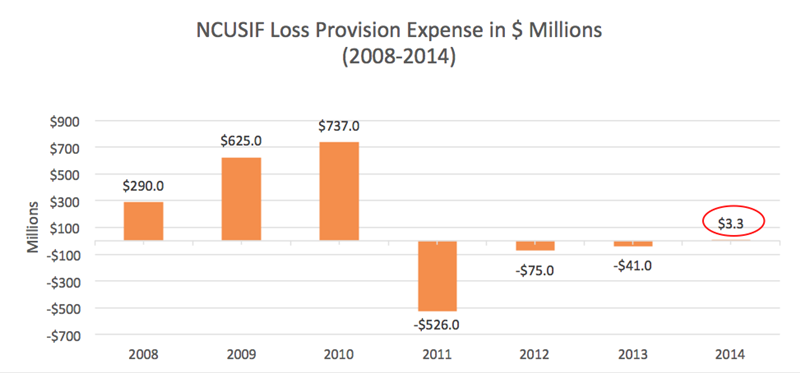

The actual cash claims paid in 2014 were $97.6 million less $51.9 million in recoveries for a net loss of $45.3 million. The provision expense was $3.3 million resulting in a year-end allowance account total of $178.3 million. As in prior years, the actual expense ($3.3 million) and the resulting loss account ($178 million) are nowhere close to the real financial loss of $45.3 million.

But the problem is more deeply rooted than accounting estimates not lining up with real results.

Another factor affecting the loss reserves are the estimates coming from the fiduciary activities of the NCUA’s office for managing acquired assets the AMAC. When NCUA liquidates a credit union, the credit union becomes an asset management estate (AME) that AMAC manages to pay out liabilities such as to the NCUSIF and creditors from assets acquired.

The footnotes describe approximately $1.0 billion in AMAC assets as follows: Fiduciary assets are not recognized in the basic financial statements, but are reported on schedules in the notes to the financial statements (note 14).

Whether this is accounting speak for we didn’t audit the AMAC numbers, someone needs to be looking at these numbers.

For example, the AMAC reports holding $97.8 million in loans and $8.4 million real estate (at written down book values, one assumes) that had the following increases in estimated recovery values: $56.3 million for loans and $3.4 million for real estate owned in the year just ended.

How could assets acquired have appreciated this much in just one year from the original book value? Or more importantly, were these assets written down by examiners when taking over the credit union only to find that these estimates were wrong by almost $60 million? Might the finding of low or no capital made during an examination have been significantly different?

The prior year’s numbers were a net of $1.5 million. Did the auditors review these dramatic changes? A change of this magnitude is certainly material and would seem an almost miraculous recovery in a short period of time. Who are the members or borrowers whose loans were taken and what is their standing in this recovery?

Estimation Errors Are Symptomatic Of A Broader Issue

According to NCUA, during 2013 (it) implemented the use of the econometric reserve model to improve the precision of the loss forecast.

The four paragraphs that follow on page 34 are reasons why the numbers will probably still be wrong:

- The loss rate is partly subjective

- Models provide a range of losses

- Judgment is used to select a point in the range

- Assumptions and methods used to estimate the anticipated losses will require continued calibration

All these phrases sound like excuses for why the agency doesn’t want to he held accountable for the numbers. If an examiner were to see the reserving patterns shown above for credit union or CUSO managers, they would rate management a CAMEL 4 or 5.

The fund’s management is the same department Office of Examination and Insurance that administers large credit union stress tests and is writing the proposed risk-based capital rule. With this record of risk estimation for its direct responsibility, how can the system have confidence in NCUA examiners’ second-hand judgments about credit union reserves and capital adequacy?

The broader issue, however, is who is managing the fund? Who reviews this seven-year track record with premiums not justified by facts, ultra over-reserving, and constant miss-valuation of assets in the AMAC etc.?

Who do the credit union stakeholders in the NCUSIF look to for responsibility? The NCUA board? The president of the NCUSIF Larry Fazio (according to page 1 of the audit, NCUA’s E&I director is also president of the NCUSIF and is responsible for the risk management of the NCUSIF)? The NCUA’s Inspector General, who receives the audit report. Rendell Jones, the NCUSIF’s chief financial officer?

Must the credit union stakeholders look to Congress or other external oversight for answers?

The Cooperative System’s Collective Capital Source

The management of the NCUSIF is about more than accounting numbers and incorrect estimates. How NCUA uses the $12 billion fund to assist credit unions in temporary downturns is critical to minimizing losses. For example, as described in Note 5, two credit unions had capital notes with net values of $47.5 million and $59.2 million at year-end. In addition, there was a senior note due from a credit union for $126.7 million.

Using the NCUSIF to recapitalize credit unions so they can restore sustainable operations can be both a necessary and cost effective policy. It is the cooperative way. With an effective supervision program, the NCUSIF should ideally never have to pay for a loss.

NCUSIF Management: Lengthening The Investment Portfolio

While NCUA was encouraging credit unions to shorten the duration of investments, the fund’s duration of its own investments has extended from 3.1 years at December 2011 to 4.25 years at December 2014. The NCUSIF’s line of credit used for systemic emergencies was $35 and $40 billion during the crisis years of ’09 and ’10 but just $5.1 billion today.

In a crisis, liquidity trumps capital; what is the plan to restore a cooperative liquidity option?

A final example of miss(ing) management: Why would the fund’s management and NCUA board set a program goal of maintaining yearly NCUSIF losses for current year failures as a percentage of average insured shares at less than 0.03% (30 basis points; approximately $265 million) when losses for the current year failures ratio was 0.0004% as compared to 0.0008 for 2013 (page 2).

Why set a performance goal for losses that is 375% to 750% higher than the actual outcome of the past two years?

NCUA’s Risk Management Track Record

The NCUA can’t seem to align the NCUSIF numbers, even in normal times, with financial reality. Its performance goals make no sense, the reserving process appears muddled if not completely arbitrary, and the management of assets acquired by the AMAC seems afflicted with the same egregious miss-estimates of value.

This is not a track record one would use to promote the agency’s expertise or effectiveness in establishing risk management ratings on every asset held by credit unions with more than $100 million in assets.

More urgently, the surplus funds used for over-reserving and funded by the 2009-2010 premium assessments are running out. The NCUSIF is not even close to breaking even on a current period versus actual events financial accounting. As shown above, the accounting positive bottom line is solely the result of reversing the over-reserving in 2009 and 2010. That well is about to run dry.

In NCUA’s 1984 annual report, which described the NCUSIF’s 1% new financing structure, chairman Ed Callahan stated: Don’t set it up and forget about it it’s your responsibility to keep it working because if you don’t, it’ll go just like everything else government touches.

Regulators live in glass houses, especially those managing credit union cooperative funds. Glass houses should be transparent. The NCUSIF room in this house has a long way to go.

NCUSIF 2014 Audit Documents Significant Management Gaps

NCUA’s proposed RBC rule presumes the agency has significant capabilities to identify future risk, document potential shortfalls, and accurately manage uncertainties.

A real-world test of these capabilities is the annual performance of the NCUSIF. NCUA released the 2014 audit on Feb. 13, 2015, with no briefing or explanatory information that would provide insight about the management of the credit union system’s collective capital.

A review of the audit results brings to light why the agency offered no insight. The accounting information obscures the real-world results and portrays an agency continuously changing its estimates in material and significant ways without explanation.

Current Period Results Versus The Official Accounting Presentation

Comparing the past seven years’ reported results with the actual activity that occurred during the year presents two very different pictures of the fund’s bottom line and overall trends.

Current period results are the actual revenue received, expenses paid, and net losses (cash paid less recoveries) incurred during the year.

The difference between the real economic/financial results and the accounting results show the NCUSIF significantly understated the bottom line in the two years of the crisis and has consistently overstated the outcome since then. Not coincidentally, the two premiums assessed by the NCUIF occurred in 2009 for $727 million and in 2010 for $930 million. Both of these current period revenue items are included in the above summaries.

From the two number series it is clear the NCUSIF has reported more positive accounting results than what the actual economic outcomes were for the past four years. During these most recent four years, the fund has had a cumulative loss of $142 million.

This operating outcome presents a different financial trend and challenge for the NCUSIF’s management than the accounting picture presents. So what is the reason for the difference? And what does this indicate about NCUA’s ability to assess, estimate, and manage its fundamental risk responsibilities?

The Accounting Re-estimates

The most important judgment the NCUSIF’s management makes is the amount to set aside in loss reserves. This is an estimate. The audit report devotes a full page to the process and describes it in three different places.

However, the data shows that the amount in the reserve account at the year-end audit date has no relation to the actual losses incurred in the fund. The most recent example is at December 2013. The reserve held $221 million, which was 485% of the actual losses of $45.6 million that were incurred in 2014.

The graph below demonstrates that year-end reserves to actual losses are all over the map, with the most extreme disconnect occurring in 2010. That year-end reserve of $1.2 billion was 1,300% more than the actual losses in 2011.

Only in 2008, when NCUA employed an auditor other than KPMG, is the loss reserve within striking distance 192% of the next year’s actual loss.

Inflated Losses Affect Accounting Numbers And Credit Unions

As every CEO/CFO knows, the primary way to increase the loss reserve is to expense from current income an amount to add to the reserve. Realized losses are then deducted as incurred from the reserve, not the income statement. Recoveries are added back. Loss provision expense is run through the income statement and is the primary factor accounting for the difference between the real operating results and the accounting numbers presented above.

For the past seven years this expense is as follows:

The problem, and the key issue for assessing NCUSIF’s management, is that this expense has shown no relationship to what actually occurred in the current or subsequent years.

The two largest differences occurred in 2009 and 2010, years in which the NCUA assessed premiums on credit unions. These premiums were not justified by the current year’s real loss experience or subsequent events. Moreover, NCUA imposed this $1.7 billion premium expense on credit unions in the midst of the financial crisis.

Just as credit unions were fulfilling their critical counter-cyclical role of expanding credit to members in the middle of the greatest financial downturn since the depression, NCUA removed $1.7 billion of credit union capital. At a 7% well-capitalized level, this expense out of capital took away $24 billion of lending potential for credit union members.

Moreover, these unneeded premiums added an expense at a time when credit unions were themselves struggling with loan losses and trying to minimize costs. Finally, NCUA transferred $462 million of these unnecessary premiums to the TCCUSF because the NCUSIF equity ratio at three subsequent year-ends exceeded the fund’s 1.3% normal operating level. The December 2014 audit of the TCCUSF shows it is also over-reserved by at least $240 million.

The chart below shows how this NCUSIF provision expense has had no relationship to actual losses throughout the past seven years. The only year the accounting event is close to real events is 2008.

2014 Audit: Dj Vu All Over Again

But surely, five years after the crisis and with the benefit of hindsight and more normalized data, NCUSIF’s management is getting better at this estimation effort.

Wrong.

The reversals of accounting estimations actually increased and had a significant impact on the reported bottom line for 2014.

The actual cash claims paid in 2014 were $97.6 million less $51.9 million in recoveries for a net loss of $45.3 million. The provision expense was $3.3 million resulting in a year-end allowance account total of $178.3 million. As in prior years, the actual expense ($3.3 million) and the resulting loss account ($178 million) are nowhere close to the real financial loss of $45.3 million.

But the problem is more deeply rooted than accounting estimates not lining up with real results.

Another factor affecting the loss reserves are the estimates coming from the fiduciary activities of the NCUA’s office for managing acquired assets the AMAC. When NCUA liquidates a credit union, the credit union becomes an asset management estate (AME) that AMAC manages to pay out liabilities such as to the NCUSIF and creditors from assets acquired.

The footnotes describe approximately $1.0 billion in AMAC assets as follows: Fiduciary assets are not recognized in the basic financial statements, but are reported on schedules in the notes to the financial statements (note 14).

Whether this is accounting speak for we didn’t audit the AMAC numbers, someone needs to be looking at these numbers.

For example, the AMAC reports holding $97.8 million in loans and $8.4 million real estate (at written down book values, one assumes) that had the following increases in estimated recovery values: $56.3 million for loans and $3.4 million for real estate owned in the year just ended.

How could assets acquired have appreciated this much in just one year from the original book value? Or more importantly, were these assets written down by examiners when taking over the credit union only to find that these estimates were wrong by almost $60 million? Might the finding of low or no capital made during an examination have been significantly different?

The prior year’s numbers were a net of $1.5 million. Did the auditors review these dramatic changes? A change of this magnitude is certainly material and would seem an almost miraculous recovery in a short period of time. Who are the members or borrowers whose loans were taken and what is their standing in this recovery?

Estimation Errors Are Symptomatic Of A Broader Issue

According to NCUA, during 2013 (it) implemented the use of the econometric reserve model to improve the precision of the loss forecast.

The four paragraphs that follow on page 34 are reasons why the numbers will probably still be wrong:

All these phrases sound like excuses for why the agency doesn’t want to he held accountable for the numbers. If an examiner were to see the reserving patterns shown above for credit union or CUSO managers, they would rate management a CAMEL 4 or 5.

The fund’s management is the same department Office of Examination and Insurance that administers large credit union stress tests and is writing the proposed risk-based capital rule. With this record of risk estimation for its direct responsibility, how can the system have confidence in NCUA examiners’ second-hand judgments about credit union reserves and capital adequacy?

The broader issue, however, is who is managing the fund? Who reviews this seven-year track record with premiums not justified by facts, ultra over-reserving, and constant miss-valuation of assets in the AMAC etc.?

Who do the credit union stakeholders in the NCUSIF look to for responsibility? The NCUA board? The president of the NCUSIF Larry Fazio (according to page 1 of the audit, NCUA’s E&I director is also president of the NCUSIF and is responsible for the risk management of the NCUSIF)? The NCUA’s Inspector General, who receives the audit report. Rendell Jones, the NCUSIF’s chief financial officer?

Must the credit union stakeholders look to Congress or other external oversight for answers?

The Cooperative System’s Collective Capital Source

The management of the NCUSIF is about more than accounting numbers and incorrect estimates. How NCUA uses the $12 billion fund to assist credit unions in temporary downturns is critical to minimizing losses. For example, as described in Note 5, two credit unions had capital notes with net values of $47.5 million and $59.2 million at year-end. In addition, there was a senior note due from a credit union for $126.7 million.

Using the NCUSIF to recapitalize credit unions so they can restore sustainable operations can be both a necessary and cost effective policy. It is the cooperative way. With an effective supervision program, the NCUSIF should ideally never have to pay for a loss.

NCUSIF Management: Lengthening The Investment Portfolio

While NCUA was encouraging credit unions to shorten the duration of investments, the fund’s duration of its own investments has extended from 3.1 years at December 2011 to 4.25 years at December 2014. The NCUSIF’s line of credit used for systemic emergencies was $35 and $40 billion during the crisis years of ’09 and ’10 but just $5.1 billion today.

In a crisis, liquidity trumps capital; what is the plan to restore a cooperative liquidity option?

A final example of miss(ing) management: Why would the fund’s management and NCUA board set a program goal of maintaining yearly NCUSIF losses for current year failures as a percentage of average insured shares at less than 0.03% (30 basis points; approximately $265 million) when losses for the current year failures ratio was 0.0004% as compared to 0.0008 for 2013 (page 2).

Why set a performance goal for losses that is 375% to 750% higher than the actual outcome of the past two years?

NCUA’s Risk Management Track Record

The NCUA can’t seem to align the NCUSIF numbers, even in normal times, with financial reality. Its performance goals make no sense, the reserving process appears muddled if not completely arbitrary, and the management of assets acquired by the AMAC seems afflicted with the same egregious miss-estimates of value.

This is not a track record one would use to promote the agency’s expertise or effectiveness in establishing risk management ratings on every asset held by credit unions with more than $100 million in assets.

More urgently, the surplus funds used for over-reserving and funded by the 2009-2010 premium assessments are running out. The NCUSIF is not even close to breaking even on a current period versus actual events financial accounting. As shown above, the accounting positive bottom line is solely the result of reversing the over-reserving in 2009 and 2010. That well is about to run dry.

In NCUA’s 1984 annual report, which described the NCUSIF’s 1% new financing structure, chairman Ed Callahan stated: Don’t set it up and forget about it it’s your responsibility to keep it working because if you don’t, it’ll go just like everything else government touches.

Regulators live in glass houses, especially those managing credit union cooperative funds. Glass houses should be transparent. The NCUSIF room in this house has a long way to go.

Daily Dose Of Industry Insights

Stay informed, inspired, and connected with the latest trends and best practices in the credit union industry by subscribing to the free CreditUnions.com newsletter.

Share this Post

Latest Articles

5 Takeaways From Trendwatch

Don’t Wait For Data. FirstLook Analysis Is Available Today.

5 Takeaways From NLCUP 2026

Keep Reading

Related Posts

Markets React To Consequential Announcements

Financial Nihilism Is Real, But How Can Credit Unions Respond?

2026 Begins With Market Sentiment Similar To 2025

5 Takeaways From NLCUP 2026

Erin ColemanMeet The Finalists For The 2026 Innovation Series: AI-Powered Member Experience

Callahan & AssociatesWhen Members Don’t Turn To FIs, They Turn To Friends And Family

Andrew LepczykView all posts in:

More on: